It was a tough few years since the war came. Until Grant, Union victories were scant; the secesh appeared to have the upper hand. In the first few years of the war, optimism was in short supply. In 1864, there was much more to celebrate and give thanks for; the mood was happier as victory and peace seemed within reach.

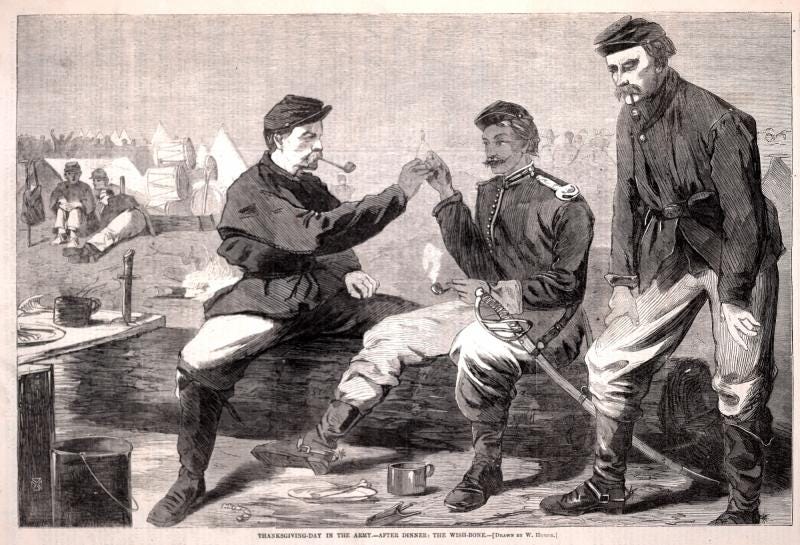

In the 3 December issue of Harper’s there were two full two-page spread drawings noting the occasion of Thanksgiving that November. The first (above) celebrated the Union soldiers partaking in the feast, and breaking a wishbone after their Turkey dinner.

According to Metmuseum, this Winslow Homer piece meant to convey a certain message

...within four months the Confederate capital of Richmond would fall and General Robert E. Lee would surrender. Superficially naturalistic, the scene is filled with objects that can be read symbolically: war drums are stacked peaceably in the background, and soldiers rest, smoke, and play, the only visible weapon a sheathed sword. The centrality of a simple game associated with a shared family feast suggests where the soldier’s thoughts are focused.

The second pictorial comes from Thomas Nast—probably the most famous and influential cartoonist of the War. In it, Nast honors Lincoln in an 8-panel drawing and who stands at the center of the piece:

The top-center shows Lincoln standing on the flag of the C.S.A. receiving huzzahs from the crowd as thanks for his executive direction during the War. There is a black woman holding her baby to the left of the President.

The lower center piece shows the generals under Lincoln. I cannot be sure but they look to be Grant (in the center, cigar in mouth) Sherman (to the left) Butler (to the right), and Rawlins or Sheridan in the background. I am not positive who the other figure is. Regardless, the army is seen as “peace-makers” in this drawing, which suggests, we must have a strong military to keep the peace, and if there is no peace, the Grand Army of the Republic will bring peace. This rendering contradicts the modern Tolstoy-like interpretation that scripture means to say that peacemakers are always turning the other cheek, and always non-violent. The proper interpretation of scripture is that peace-makers are compelled to violence to secure it. Sometimes, defense, and violence, is necessary in order to live in peace.

The other frames are ones that thank God—upper left, and upper right. The upper left thanks God for Maryland freeing her slaves, with Columbia bestowing her blessing upon black families. The upper right is Columbia, once again, with her shield and sword on the floor bowing before her throne, thanking God for Union victories.

The center left and right are Europe and the Rebels, looking somewhat discouraged that their fortunes are diminishing. The rebel pane shows Alexander Stephens and Robert E. Lee concerned and depressed.

Finally, the lower left and right thanks the Army and the Navy for their efforts. The Army and Navy began tightening their hold over the confederacy. Surrender was imminent.

A comparison of Nast’s 1863 v 1864 depictions of Thanksgiving shows in the former, sadder scenes with people beseeching God. The 1864 representation is most definitely more optimistic.

Happy Thanksgiving to all and many blessings for the coming year.