I have mentioned this book on my youtube channel and promised a review of it.

The auto industry’s development was arguably one of the most important manifestations of the 19th-20th century that freed man from his time and place—in some ways that IS a drawback, but in the realities of the industrial age, it meant man had at his disposal, a tool of liberty to relieve his estate and not be trapped by local prejudices, or other confining local realities, that prohibited him from earning all he could by the sweat of his brow.

Enter David Lucsko’s excellent little book Junkyards, Gearheads, and Rust to remind us where we started, and what transpired to saddle us where we are now.

We cannot help but admire the people of a more hearty time, who in all their manly ambition, risked name and reputation to create something that would, in fact, help in real terms the average American, even if the industry began as a rich man’s toy. It was never the intent of people like Henry Ford to benefit people of a certain class. He wanted his cars (and tractors, trucks) to be useful to those in the country as well as the city.

This book is not necessarily about such grand cultural effects of the auto, however. It talks about the meaningful car culture that grew up around the automobile. By that I mean gas combustion engines. Battery powered cars, and steam, were a miserable failure, though each had their advocates (cult like followers?) even then. Even Ford dabbled with the electric car and Ford’s good friend, Thomas Edison, tried and failed to make a reliable electric vehicle (same as today).

Regardless of the power source, this book is about the culture of repair, fabrication, and, yes, environmentalism in reusing old parts for their intended purpose, or for using them in unique ways that contributed to hot rodding (Motorcycles also had this culture). Lucsko details the rise of hot rodders quite well.

As the author makes clear, no one restored their vehivles between 1890-1920. Most cars were scrapped or found in the salvage yard. While someone might “refurbish” their auto, they did not exactly “restore” it.

Most cars between 1900-1920 were simply abandoned—left on the side of the road or in parking lots. However, by the early 1900s there were stories in the prominent magazines of the day (like Motor Age) that got excited at “barn finds” from the late 1890s, and one steam engine car from 1855! The salvage (and towing) business grew out of the abandonment of cars left for all to see. In fact it was because of this abandonment problem that the tow-truck was invented.

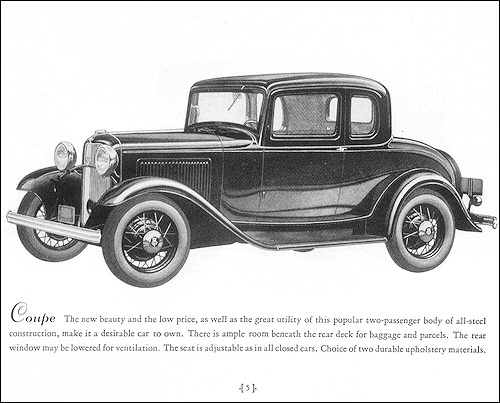

By the 1930s, restoration became a more popular vocation to preserve what was made the previous 20-30 years for posterity. Most of these hearty attempts were not from the elite classes, but came from the lower income brackets who had mind and talent to do real work. It was them who preserved our memory.

The greatest resource to restorationists was the salvage yard where the location of parts could be found and reused. By the 1950s it was the yard where one could even find enough of a complete car to restore. This was more the case for mass produced cars like the Model A or T in the beginning, but was possible through out to the 60s.

Through the 60s-80s an enterprising person could find a Mustang or Camaro in the pick & pull. Good luck finding one of those now. If someone finds a classic car today, it will likely come from places like Arizona (because rust free), or be some kind of “barn find”—a car stuffed in a barn and forgotten for generations. However, that market was pretty much exhausted by the end of the 90s. Finding one now would be a rare find indeed.

The Assault on Older Cars

The attack on not only gas engines, but classic cars of all stripes, came from the environmentally hostile state of California. In the 1990s Lucsko details the attempt to run any old and its preservation out of our memory.

By the 1990s-2000, salvage yards began to close. Why? Because of the federal regulatory environment and insurance companies making it expensive to operate. The latter was in no doubt caused by the former. That was by far the greatest blow to the salvage of old cars. But, nothing outlasts time, according to the author, and Nature. That is, no matter what, we all return to dust.

In American Graffiti, the 1973 movie reminisced about the golden age of hot rodding, and a general manly spirit for speed and girls. By 1973, that spirit and nostalgia was doomed. Lucsko does not draw this connection as completely, but he describes how the era came to a close and the nostalgia for the era in a time of increasing complexity of modern life. All those who were looking for a simple time in that 1973 film were escaping the real decline of the American government—that is the framing of Richard Nixon by the ruling class, and the emasculation of men. Everyone saw (or felt) a denuding change coming. This is why the movie was such a hit—it was a last gasp of American liberty.

The decline of the salvage yard is no different. It is but one of many examples of the decline of American life.

For the 1950s it was the resurrection of the 1930s. For the 1980s-90s, it is the resurrection of the 1960s. For the present, it is the resurrection of the 1980s. All these era seek to preserve something of quality and spiritedness of the American Idea. For all real practical purposes, the era of real vehicles ends in 1986. The author does not make that argument, so I want to be clear I am. There is no real restoration of modern vehicles from the 90s. No one stops to look at a vehicle made from 1990 onward. I have been to many a salvage yard—no one is looking to do anything with a vehicle in the yard except get a part to keep something on the road; they are not trying to make their vehicle look like it once was.

If there is one thing that the salvage yard represents, it is gold. For many, it is a trip back into the way things were, not because of nostalgia, at least not simply, but because we made things of higher quality, that looked better, sounded better, and appeals to the sense of our human existence.

All this ended up making our cars sicker.

From the 1960s to the present we find a highly organized assault mostly driven by government, and leftists, to snuff out any avenue men might have for creating manly things. It all started with the LBJ administration’s Highway Beautification act (1965). And just what was the issue at hand? The ugly salvage yards that existed long before people started moving into an area where a salvage yard existed. The people seeking to leave the poorly managed city, then applied the same regulations from said poorly managed city on people who had lived in an area for far longer than they. They moved near a salvage yard by choice, then instead of taking responsibility for their own decision, sought to violate the property rights of the salvage yard owner. Lucsko does not write like that, but he should have, because it is true. So, of course, the salvage yard has to go, your property rights be damned.

Lucsko captures the intellectual issue nicely:

“Perhaps these sorts of conflicts over land use, property values, and beautification amount to nothing more than an American farce, complete with country bumpkins, blue-collar ruffians, snooty yuppies, and unscrupulous politicians. Or perhaps they merely represent another chapter in humanity’s long search for the “ultimate sink,” a place to dump those things we deem unsightly or unclean—in this case, out-of-service combines and clapped-out cars. But if we dig a little deeper, and if we really listen to what the actors in these stories have to say, we might not be so eager to brush them aside. For at their core, the many disputes over neighbors’ cars, neighbors’ yards, and neighboring junkyards that have played out over the last fifty years reflect not only here-and-now concerns about property values and eyesore mitigation but also a lingering divide within American culture over the meaning, value, and broader implications of a way of life geared toward obsolescence. Put another way, these stories present a clash of worldviews centered broadly on the relative merits of the old and the new.”

The Act however was a miserable failure because it relied on states for enforcement. The states checked this federal accumulation of power, and said, no. The ruling class was not pleased. So they tried again. The Not in my Backyard phenomenon was strong. Therefore, the assault gained steam rather than succumb to failure after 1965.

Local government began exerting their authority to drive not just salvage yards, but the backyard mechanic, out of existence. People sought to ban “ugly” vehicles from sight. Regulation and ordinances were drawn up to accomplish the deed. When car enthusiasts complained, the govt expert said “you misunderstand we are trying to scrap clunkers not classics.” But this is illogical since clunkers WERE CLASSICS.1

For salvage yards, licensing, and environmental regulations were employed. Salvage yards may contaminate the ground and the water beneath you see. Therefore, increasing fees and fines were levied upon them, not for the environment of course, but to drive them from business.

But more: the federal govt figured out a way to help get rid of older cars, and also saddle us with inferior products: the emissions regulations. They made up a crisis that vehicles were great polluters, and went after strapping engines through a whole host of means—emissions in particular. They also forced companies to meet mileage requirements. All this ended up making our cars sicker.

Lucsko does not tie together just when the states began cooperating with the national government, but it did happen, and in tandem, the individual was left powerless for the most part. In fact, one could say the mass of mankind was blind to exactly what was happening. I include myself in that criticism.

In California, a program began to crush old cars—in the name of the environment of course. The various Clean Air Acts passed in the 90s and beyond were the vehicle to accomplish this job. Scrappage was incentivized if not outright mandated. Yet, it is not clear really how successful any of these scrap programs were, one thing is for certain, the regulations on new vehicles that manufacturers were forced into compliance, made the scrappage of older cars virtually guaranteed.

What we have today is a similar set of cars that all look the same. There is nothing distinctive about our modern vehicles. There is no beauty, only sanitized creations that we have no real care for. This is what the older cars shared with Horses: we actually carted for our things and took interest in them, how they worked, and how they performed.

The decline of individual agency (as I wrote about in another post here), has been perhaps the real aim of all this, not some environmental goal. After all, science is split on the effects of vehicle exhaust enough to cause measurable damage much less destroy the earth. Lucsko is not wrong when he writes, “we litter less” now, but “we waste a great deal more.” The Green movement is a complete farce.

Lucsko’s book is a great reminder that the things we take for granted, and perhaps think as small matters, are actually part of a larger trend to control the adventurous spirit. While he does not draw the development of the car enthusiast culture’s slow demise as anything so nefarious, it is hard not to draw those connections oneself.

Increasingly, the battery phase (which has little practical support) is all proprietary—it will effectively end men working on cars; it will end the garage; it will end backyard maintenance. How? Telsa for example, prohibits anyone but them to work on the car. Convenient, yes? This is not an anomaly, it will be a trend.

The war on classic cars was in fact a war on men and their spiritedness. In the process, we lost the skills, and beauty, of a better time. It all began when this country went to war on the salvage yard, and the older classics they contained.2

Honestly, it is up to the restorationist to determine what is and is not salvageable. The govt really has no place in it, but then again bureaucrats had an agenda to complete.

Just as I was about to publish this, I was made aware of a few salvage yards dealing in older cars back to 1928—but these are far and few between and more less, open secrets.